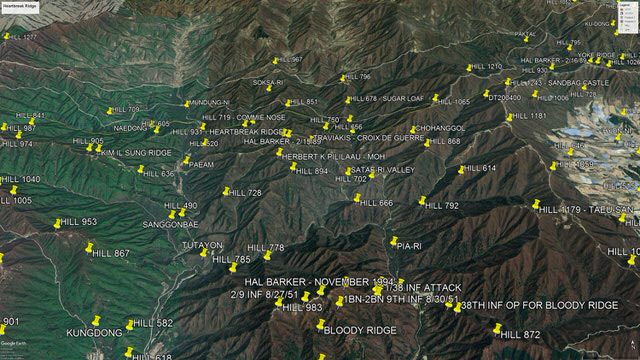

Return To Heartbreak Ridge

A Journey Into The Past

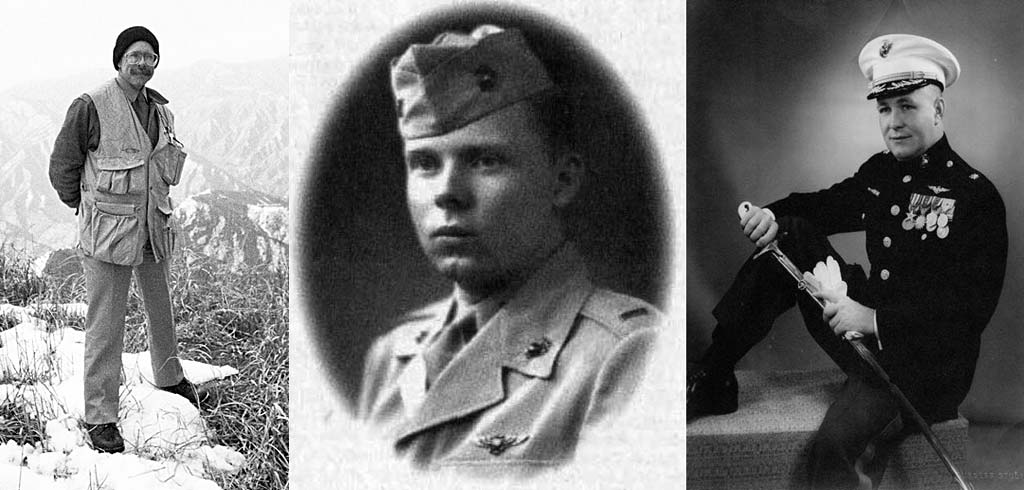

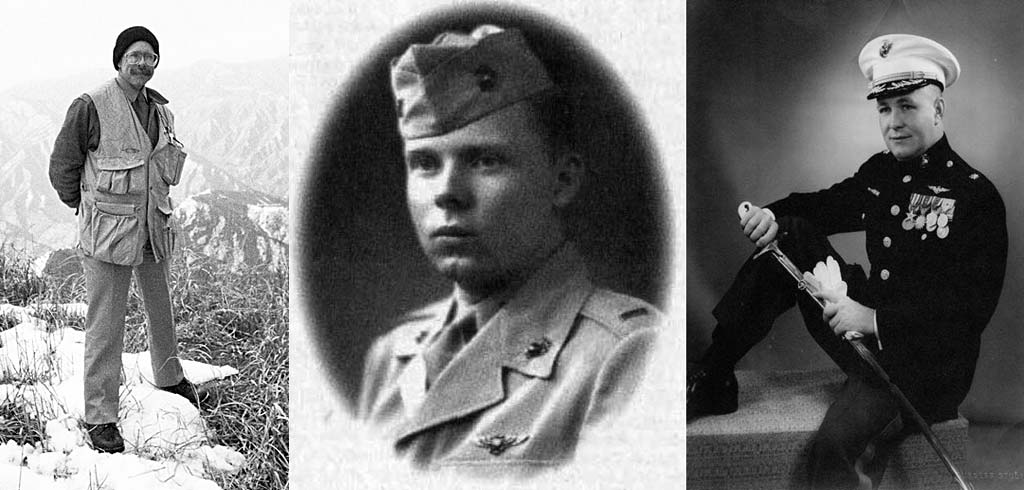

Hal Barker - Dallas - Texas

Purple Heart

I leaned back and threw the medal high in the air. The wind caught the symbol of blood spilled. The token of war sailed out of sight down the face of Heartbreak Ridge. The South Korean Officers with me applauded, and then became silent. We had our thoughts. I looked at my watch. It was 5 P.M., February 15, 1989. I couldn't feel the wind or the cold.

I was thinking what happened here, right here on this mountain, in the bitter fall of 1951, during the Korean War. A young Marine Corsair pilot, of Chicago, was hit by friendly fire over Heartbreak Ridge on October 7, 1951. His aircraft exploded, a wing came off, a parachute opened.

An urgent call came in to the operations tent at Marine Observation Squadron Six a few miles to the southeast of Heartbreak Ridge. Major Edward Lee Barker of Crockett, Texas, volunteered to attempt a helicopter rescue.

The Silver Star citation reads:

"...Making his way through a heavy artillery barrage, (Major Barker) bravely pressed on toward his objective and although his aircraft was hit and damaged, carried out three daring attempts to pick up the downed airman, returning to base only when it became apparent that rescue by helicopter was impossible..."

The Colonel

We stood on the apron at El Toro Marine Corps Air Base in September 1951, watching my father leave for the Korean War. I was almost 4 years old, a Marine brat born at Aiea Naval Hospital overlooking Pearl Harbor.

On that same transport plane was another Marine pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Arthur D. DeLacy. I have only the barest memories of the concrete, the smell of exhaust and the noise of the engines, the steps up to the aircraft, the control tower to my right, my mother holding my hand, the warm California sun. I was too young to understand what was happening. I would learn years later what it meant.

The Colonel I knew from photographs wore his medals well. And proudly. But without words. He would not talk about Korea, or really much else. I grew up with him, watched him, but knew nothing abouthim. Nothing at all. He was the Colonel, and I was the younger son. We were glad years later, when he went overseas again, it was a respite from order and discipline. My older brother took the brunt, nothing was expected from me. I lived my own life, deep in books. I was ignored, and I seemed to like it that way. I paid a price I could not afford.

My father would never talk about the medals on his dress blues. I found out for myself. A letter to Headquarters Marine Corps in 1979 brought the copy of his citation. I let it lay for a while.

It was tough growing up the son of a United States Marine pilot. I was a sickly child, with asthma and allergies, and all that goes with being sick a great deal of the time. I would strike out at baseball, and dad would yell at me as if I was an idiot. Coach put me in right field. I vividly remember my last baseball game at ten years old, Kingsville, Texas, when the fly ball landed at my side. I picked it up, threw valiantly, and struck the runner in the leg. Another error for Hal Barker, and I never played ball again. Later, the doctors at Camp Lejeune would find I was almost blind, and prescribed thick glasses.

In reality, I gained breathing space. I learned to smile and to take things easy. Most importantly, I learned to laugh at myself, that tough little kid in right field.

Twenty years later, I would read a book by Pat Conroy, The Great Santini. It was as if Conroy had gotten inside my head, telling the story of a Marine fighter pilot and his family. I put the book down, and called my father for the first time in years. I wanted to finally resolve a conflict. I flew to San Francisco a few days later, but it did not work out. He was still the Colonel, and I was the little kid who always struck out.

I didn't give up. In 1982, the Colonel and I finally talked about Korea.

"It was a case of getting up in the morning before daybreak, flying missions, coming back, sleeping when you could, and flying missions..."

"I wasn't a hero. I was scared. Medals were a dime a dozen. It was unbelievable what we did out there. It was the beginning of helicopter warfare. But medals were not just given, they were earned."

"I saw DeLacy. I knew him. He was lying flat on the ground. His parachute was beside him. We figured he was tied down, or severely injured. He may have been a decoy. I hovered over him, and we were hit by small arms fire. I went down into a valley while our aircraft strafed the area. I went back three times, and the third time we called it off, the F4-U's in the area had to go home, they were out of ammunition."

" I couldn't get him."

Gaither Nicholas

In 1982, I wrote a letter to the editor at the Denver Post looking for veterans of Heartbreak Ridge. A woman called early on a Sunday morning. She had seen the letter printed on the editorial page. She wouldn't give her name. She told me she sent her husband out on an errand to give her time to call. She told me how sudden noises triggered him 30 years after the war. How he always looked at the high ground when they drove in the mountains, his eyes darting around, nervous, sometimes sweating. It was all unspoken, held deeply inside.

I discovered most Korean War veterans would not talk to their families. Maybe they thought we would not care, could not understand. The wives and children were shut out.

A letter to the U.S. Army Chief of Military History brought a suggestion to contact the 23rd Infantry Regiment Association, Korean War Branch. The 23rd Infantry, attached to the Army Second Indianhead Division, captured Heartbreak Ridge.

A return letter invited me to the annual reunion of the 23rdInfantry at Port Washington, New York, July 1982. I was a field carpenter, considered by most to be a loner, and certainly not a candidate to pry into the lives of military veterans. Something pushed me to learn more about Korea.

I put on a three-piece suit, and flew to New York. The taxi dropped me at the American Legion in a tiny drab storefront. Inside, it was at least 100 degrees. I was disorientated, not knowing what to say or do.

Several of the veterans stared at me, obviously wondering who I was. Someone offered me a beer, and suggested I speak to Gaither. On that overwhelmingly hot summer day, I met Gaither Nicholas, a tobacco farmer from Crossville, Tennessee, a man of gentle power.

I put my coat on a hanger. We shook hands, and sat down at a long table. He pulled up his shirt. Holes in his body ran diagonally from waist to shoulder. He was bluntly telling me what war was about. He was trying to shock me. Challenging me to say the right words, demanding from me a reaction, showing me the brutality of war without speaking.

Gaither and I talked about his bitterness after the war, his uncontrolled violence, the pain of wounds which would surely killed a lesser man. We talked of his moments of oblivion at Heartbreak Ridge. His words touched me. Gaither was hit just yards below the peak of Hill 931, shot by a North Korean with a burp gun. Point-blank.

He was a working man, showed me his hands. I held out my own rough hands, showed him the cuts and burns. I think he was surprised. The day before, I was sweating in a hole in Colorado, pouring concrete for a home I was building. I've been a carpenter since college, and proud of it. Some would say I was a misfit.

Nicholas sensed something in me, for he began to tell me his feelings. After Korea, he admitted, he had been a violent man, vicious, unyielding, unforgiving, unrepentant. Drink became his life, and a hell it was for his family and neighbors. After 1970, he found strength within and became a human again. But people don't forget. The past is not easily forgotten.

For Gaither Nicholas, war was not abstract. War was real, and he was determined to force me to deal on his terms, with his bulletwounds, his fears, his dreams. He attacked me head on, forcing me to deal with his pain. We talked as only strangers can, with a sense of urgency, sometimes both at once, as if no time remained.

Colonel James Dick told me Gaither Nicholas was one of the finest men he had ever known. Jim Dick knew Gaither as few men can know one another. Gaither was with Alpha Company on Heartbreak Ridge, and Jim Dick was his company commander, the man who ordered him to kill.

Later, I sat at a table of several veterans of Heartbreak Ridge. We talked generally about the 30 day battle, then I asked if anyone remembered a helicopter rescue. They remembered the rescue, all right. One veteran recounted the helicopter rushing over his position, another vividly described the sound of the bullets hitting the hovering aircraft. A third veteran told of cheers when the chopper flew off toward base.

I told them my father was the pilot of that rescue helicopter, and that the downed pilot was killed. It became very quiet, and I could not talk. The veterans were silent.

The Korean War Veterans Memorial

And now, in 1989, I was spending eleven days in South Korea almost four decades after my father served there. I had taken my Christmas bonus pay and bought a ticket on Korean Air Lines. The Korean War drew me like a magnet.

My father did not know I was going to his battlefield in Korea. We don't talk much anymore. I guess we never did. I guess we never will. It will always matter.

1984, I founded what would become the national Korean War Veterans Memorial Fund. By that time, I had learned about the silent treatment given to Korean War veterans, and I was angry. In trying to find out about my father, my eyes were opened to a forgotten war. I could hardly believe few cared.

David Christian, of Washington's Crossing, Pennsylvania, a lawyer and highly decorated veteran of Vietnam, set me straight. Christian said to stow the anger, think positive, think logically, hold it all in, make it happen. Christian was right, of course.

A great deal went on behind the scenes .

Congress wasn't sure about a Korean War Memorial. A telephone friend, Bill Temple, of Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, decided we would confront Congress in April, 1985. Temple saw vicious combat in Korea serving with the U.S. Army 38th Infantry Regiment. We met for the first time on a Friday morning, and set off for Capitol Hill.

With only one day to convince key members of the House of Representatives that a Korean War Memorial should be built, we literally ran from office to office. One aide was rude, and I thought Temple would explode.

Days later, the Korean War Memorial became an issue in the House of Representatives. A month later, Temple and I returned to Washington to lobby the Senate. I used my mortgage payment to pay for the plane ticket. By this time, I was obsessed.

President Reagan signed the Korean War Veterans Memorial Act into law on October 28, 1986. I played a small part alongside hundreds of common Americans who refused to forget Korea.

North Of Yanggu

The South Korean government finally agreed to let me go to my fathers' battlefield at Heartbreak Ridge. I left Dallas on February 10, 1989.

At the South Korean Ministry of Defense in Seoul, I met my escort officer, Lieutenant Kim Won Hyung.

We set off for Heartbreak Ridge in a Ministry of Defense sedan. Three hours later at Chunchon, it was lunch time. In Korea, life stops for lunch. Lieutenant Kim was surprised I could handle chop-sticks so well. I didn't tell him I had only used the sticks twice before, or that I was new to Korean food.

From Chunchon, we left the paved highway, and for 74 kilometers bumped and crashed along a rough dirt Korean mountain road, the same road North Koreans used to attack South Korea in 1950. We arrived at our destination, Yanggu, late in the afternoon.

At the 24th Tiger Division, I met the commander of the unit defending Heartbreak Ridge. The Koreans were all very cordial and offered me ginseng tea. We made small talk, but I was sitting on the edge of my seat.

Eight of us piled into two Jeeps and set off. Passing tank traps, emplacements, more tank traps, we entered a narrow valley only a few yards wide. The Suipchon, only a creek, was frozen. It reminded me a great deal of Boulder Canyon in Colorado.

A sign ahead said Loaded Weapons Area in English. We stopped at a barricade and were issued blue armbands of the United Nations Military Armistice Commission. Soldiers placed a blue flag on the bumper of the jeep.

The Korean Intelligence officer with me asked me if I were nervous. I blurted out something incomprehensible, and he smiled.

The jeep ground into first gear. We bumped up the rough dirt road. Snow lay only on the northern exposures. The single lane followed the creek bed. This was no highway, just a track. It took more than courage to fight up this road in 1951.

After climbing higher, I sighted an observation post outlined on a ridgeline. It was rugged country. We lurched into a parking area behind the positions on the military crest.

A flat space was plowed on the ridge, and a series of concrete bunkers were built. We all trooped out from the Jeeps. I was here, where my father won the Silver Star. By this time, the Koreans were as excited as me.

A glassed-in observation room rested on a forward slope. I remember we had to climb up several very high steps, then across an open space to the room. Inside, a Captain served ginseng tea.

Through a camouflage curtain lay North Korea. In shock, I looked out to the place where my father flew his helicopter 38 years earlier. All of us were talking at once, pointing here and there in total confusion.

They understood me.

Lieutenant Kim suggested we climb atop the observation post, so we all grabbed the rails. I was still in shock, but I set up my Nikon on the roof and took a photograph after the Korean intelligence officer looked through the lens.

The Koreans seemed to understand I wanted to be alone, so all but one officer went below. I stood there in the cold winter wind, burning into my mind the emotion I was feeling.

I could see forever from where I stood. Rugged mountains stretched in all directions. I wondered how a man could fight for this place and retain his sanity. The ridges were razor sharp, no more that three or four feet wide, sloping upward at angles of 45 to 60 degrees. The 23rd Infantry scraped and pulled themselves up thousands of feet to capture the high ground under withering fire. It was unbelievable.

Hill 931

Hill 931 was 150 yards away, and I asked Lieutenant Kim if I could climb to the peak. The Korean officers with me started to climb ahead, but I rushed past them in great haste. I made the peak. I was living a dream, and the Koreans understood. Later, Lieutenant Kim told me my face looked very cold and drained, as if I had shut out everything and everyone.

I was standing 600 yards inside the Demilitarized Zone at a point where no American civilian had stood since the war. Lieutenant Kim told me no one else would be allowed to make this trip. He said, "This trip is just for you. We wanted it to happen just for you. You will remember our country."

The top of Hill 931 was flat for only a few square yards. A steel identification panel faced toward South Korea. I asked Lieutenant Kim if I could bury the Purple Heart on the peak. One of the Korean officers brought an entrenching tool, but he unsuccessfully banged away at the frozen ground. Lieutenant Kim came up to say the officers would bury the medal in the spring-time, the ground was frozen now.

I asked him if I could throw the medal off Hill 931. The lieutenant spoke with his comrades, and they said, "Yes, it would be an honorable thing to do."

The Koreans said I would be throwing the medal into a mine field, that the medal would lay there forever, a reminder to them that America had fought for South Korea at a place called Heartbreak Ridge.

Through the deep snow, I walked back to the bunkers. Lieutenant Kim said the commander of the ROK unit on Heartbreak Ridge would like to meet me if I wished. I said, of course, and we filed into a small room on the peak of the ridgeline. The commander gave me a gift of Buddhist prayer beads, and a leather snap ring of the 24th Division.

Down from Heartbreak Ridge, the Intelligence officer asks me how I felt. I can explain nothing. I walk around the question. A few minutes later, I ask him the same question. He tells me it is too complex to discuss now, we need to talk much later.

From Yanggu, our Korean Marine driver drove Lieutenant Kim and I to the Korean east coast where we would stay the night at Sok-chu. We arrived at a huge condominium project, and checked in. Lieutenant Kim and the driver were still formal with me, still not understanding this strange American who had come to stand on mountaintops in Asia. The Koreans were not used to an American so willing to understand their country and their customs.

Punchbowl

The next day, Lieutenant Kim and I set out for the Punchbowl and the location of X-83, the airstrip where my father was stationed with the First Marine Air Wing in 1951.

The Punchbowl is a natural geologic bowl several miles across, ringed by steep mountains on three sides. The bowl creates the richest farmland in South Korea, and the area is starkly beautiful in winter.

A week before leaving for Korea, I received a letter from Mrs. G.H. "Tommie" Johnson of Dallas, Texas. Her son, Corporal Charles F. Lehman, 5th Marines, First Marine Division, was killed September 25, 1951, in the Punchbowl area. She wrote.

Dear Mr. Barker,

This is the ribbon that was tied around his high school diploma 'Sunset High.' My daughter asked me to send her regards and thanks.

She is married to the Marine who was with my son when he was killed.

Thanks again for all you are doing.

Sincerely, Tommie.

I carried the long purple ribbon in my breast pocket. In a Jeep again, we climbed in low gear through deep Korean mud. Our final destination would be far inside the DMZ, on a crucial defensive ridge facing the North Koreans.

Two lines of fences and barbed wire stretched in both directions. Republic of Korea troops in winter white uniforms constantly patrolled the wire. I was given a briefing by Captain Lee regarding the disposition of troops in the sector before me. I could see stone markers delineating the border through the telescope. To my right, United Nations and South Korean flags flew side by side.

Kumgang Mountain, a mystical point in Korean life, lay off to the northeast, shrouded in mist. All the officers pointed out toward Kumgang as if pointing in itself would will away the mist. One ROK officer told me in broken English that he would like to go to Kumgang Mountain with his children in a country where war was a forgotten word.

A cold wind blew when I left the observation point. Sleet was falling, and the view into the Punchbowl was swirling with signs of winter. I stopped for a photograph with the Korean officers, then it was back into the jeep for the trip down.

I had forgotten about the purple ribbon in my haste to take in everything. Captain Lee asked where I would like to leave the ribbon. I jerked into reality.

We drove on until I saw a promontory. I recall feeling very strongly this should be the place. The Korean officers jumped out and raced through the ankle deep snow up and to our right. The sky was gray, the wind was blowing, it was late in the afternoon. I held the ribbon high in my hand, the wind carrying it straight out from my body.

I let the purple ribbon go with the wind.

The Hoppy Harris Letters

Originally, I was trying to find out about my father. I wanted to know what made him tick. I had no idea that my search for my own roots would become so complex. I should have known.

Many veterans and their families contacted me. Each day, the mail brought a new story, a new direction, a new awareness of the war. I was constantly told that no one had asked questions about Korea before me.

It was indeed "the forgotten war."

I received a letter in 1982 from Seymour "Hoppy" Harris, a machine gunner with Company H, 2nd Battalion, 23rd Infantry, Second Indianhead Division. The letter, postmarked Macedon, New York, was short and to the point. I didn't answer for several months. His return letter started a chain of events which drew me into the Korean War in a way I never imagined.

"Dear Hal,

We were in reserve when we got the word to saddle up. We were going back on line. When I reported to the 1st Lieutenant I was to go up with as support weapons, I asked him, 'What's the deal, Lieutenant? How's it look?'"

"Nothing to it," he said. "Seems they got a bulge in the line, we will straighten it out. Piece of cake."

"I remember one night in particular they gave it to us with rockets and I lay in the bottom of a foxhole all by my lonesome and screamed.

Oh God, Oh God, I've had enough! I've had enough! Oh God, I've had enough!

Oh merciful Jesus, I've had enough! I've had enough! Oh please help me, I've had enough!"

"The papers called it "Heartbreak Ridge."

Back home in Dallas, I stare at a stack of letters a half-foot thick on the desk in front of me, all hand-written letters from Hoppy Harris.

Some reach 40 pages. Long ago I discovered Harris had a photographic memory frozen in Korea. Years ago, he sent me his Purple Heart. It was this same Purple Heart I left on Heartbreak Ridge.

Harris became a symbol of the Korean War to me. He joined the 23rd Infantry for the first time at an obscure crossroads town called Chip-yong-ni on the morning of February 13, 1951.

Hoppy Harris, an untried replacement, was on one of two trucks full of supplies and replacements. Unknown to Harris, the trucks would be the last vehicles into Chip-yong-ni before almost 4500 American, French and Korean soldiers of the 23rd Regimental Combat Team were surrounded by elements of five Chinese divisions.

Harris wrote of his journey into war.

"We are the only trucks moving north. We also notice there are no units on either side of the road. It is as if we are the first men on the moon. I don't notice the cold so much. My eyes scan the low hills to our right."

"We barrel-ass! We have to lay down and curl up in a ball, the wind hitting us is like a knife. We go like this for maybe three or four miles, then slow down and finally come to a halt with the trucks' left wheel in a ditch."

"When I raise up to look around, there is a village or what is left of one, and GI's all over the place."

"Someone asks a passing soldier where the hell is this place?"

"Chip-yong-ni."

Chip-yong-ni

Exactly 38 years later to the hour, I was with Thomas M. Ryan, Command Historian for the United States Eighth Army in South Korea, an archeology graduate from Southern Methodist University. We were on our way to Chip-yong-ni, 60 kilometers east of Seoul. We would be looking for Hoppy Harris's position on the Fox Company perimeter.

Harris, in another letter, wrote of his first night of combat.

"I'm in a machine gun bunker and it is cold. Brutally cold. It must be below zero, but seems colder. There is not a cloud in the sky, and if you walk around the snow creaks under your feet. This is good, for if it creaks under our feet, it creaks under theirs."

"We are at the mouth of a draw, and barbed wire stretches across our front."

"Way off in the distance to our left front I hear a fire-fight break out. The sky lights up like heat lightning as some sort of shells explode. Faintly I hear the sound of a bugle. Now and then I hear awhistle."

Ryan parked the car alongside a road. We grabbed our gear, including a metal detector. Harris had described a footpath leading to a saddle between two low hills.

Today, February 13, 1989, I was following the same footpath in an area virtually unchanged. The saddle was clearly evident. I felt strongly that I had been here before. Harris had described the area exactly. We easily found Harris's position.

I had gone over the topographic maps and aerial photos a thousand times, but I was surprised how small the killing ground appeared. I found it remarkable how exposed the American positions were to theChinese.

Harris described his second night of combat.

"Night comes. I have not been in the unit but for a few hours, but somehow I feel a sense of urgency. I feel it. Something is going to happen."

"I admit I must have dozed, because I recall snapping my head up and looking up the draw. I see the Chinese coming, but at first it doesn't register on me. I look away. I thought, God, they look like ghosts! The draw is full of them. They are about 100 yards from the wire. They come silently, like little clowns. There is no chatter. The night is still as death. On and on they come."

"The first Chinese hit the wire. Sgt. O'Shell fires, and it is like every weapon is wired together. They all go off at once. Tracers like laser beams streak out and I see them cut clean through the Chinese. I hear them scream, and they go down like stalks of corn before a corn cutter. It is only seconds and the mortars start to rain in. Artillery follows, and the draw becomes an orange-grey hell. The noise is deafening. Beyond description. I am frozen, spellbound by the sight and sound of it. Slowly the battle subsides, the Chinese pull back."

"I really have no idea how many we killed that night. I heard 500 or more. All I know is that the draw was littered with dead as far as I could see."

Tom was busy with the metal detector, finding several .30 caliber bullet casings along with one live round. Pieces of shrapnel were everywhere in the ground just below the surface.

I walked a few feet out into the open area where the Chinese hit the wire. I felt melancholy, and it was almost oppressive. Hundreds of men had died exactly where I stood now on the bank of a rice paddy, hit by grazing fire from the machine guns.

Today, in 1989, I could hear the sound of children's voices in the distance.

Tom and I set off to scale the high ground on Hill 397 south of Harris's bunker. Climbing a small path late in the afternoon, we pushed through brambles, fallen trees, and rocky outcrops. The path gave out, and we turned west just before the summit. On the ridgeline, we could see the entire perimeter once held by the 23rd Infantry. The Chinese had complete observation of the area.

Darkness fell, and we were still high on the mountain. It was dangerous, for Chinese fighting holes and bunkers covered the area.

Eventually, we were able to find a path, and dropped down into a small village. In the town of Chip-yong-ni, two very tired men stopped in a small coffee shop heated by a wood stove, at a crossroads in Korea.

Ryan and I walked through the town at sunrise the next morning. School children filled the streets, making long shadows on the pavement. Thirty-eight years a go, on these very streets, shells exploded in one of the most vicious battles of the Korean War, or any war for that matter.

The siege of Chip-yong-ni was broken on February 15, 1951, when tanks of the 5th Cavalry Regiment approached from the southwest and entered the perimeter. Thousands of Chinese bodies littered the area around the small town. Ammunition was down to a handful of rounds for each soldier, and the situation was beyond desperate.

The successful defense of Chip-yong-ni by combined United Nations forces under Colonel Paul Freeman broke the back of the massive Chinese winter offensive in that sector of central Korea.

May Massacre

After Chip-yong-ni, the 23rd Infantry pushed northeast until May, when a defensive line was established, the "No-Name Line." On May 16, 1951, the enemy began probing attacks across a broad front in preparation for an offensive operation. Elements of the 23rd Infantry were on the high ground of a mountain mass called Kari-san, Hill 1051, near the village of Chaun-ni, Republic of Korea.

Sergeant Phillip N. Bailey, F Company, 23rd Infantry Regiment, was located on a knoll just to the east of the main peak of Hill 1051.

Today, Bailey is a retired General Motors automobile worker living in Mechanicsburg, Ohio. The day of May 17, 1951, stands out forever in his mind. Bailey wrote,

"The early morning of May 17 seemed different. The relaxed mood (of earlier days) was gone. About one hour after daybreak, one of our observation planes went over our position and on over Hill 1051. He was not gone long before he was back over us. He dropped us a message. It said, 'Enemy out in front of you in regiment strength.'"

"He flew back over 1051. He was back shortly with another message,

'Maybe two divisions of enemy.'"

"He made another trip over 1051. His last message said, 'I can't see the end of them.'"

Chinese troops began to move over the ridgeline and to the left rear of Bailey's position in a trickle, but soon grew to a flood. Hundreds of enemy were visible at any one time, and shots from the F Company troops did not seem to bother them. Bailey continued in his letter,

"Sometime that afternoon, after thousands of Chinese had passed us going toward our rear area, we heard some big guns open up toward wherethe Chinese had been going. More and more guns joined in. The battle looked at least a mile behind us and to the left."

"The hollow became red from the explosions and a continuous roar could be heard. We were happy that someone else had brought the Chinese under fire. This soon caused us a problem that we had not had before.

The last 200 or 300 Chinese that had gone by us were coming back uphill to get away from those guns. They were meeting the tide of Chinese coming downhill. This caused a log jam out front of (our) outpost of more Chinese than we knew how to handle."

"Late in the afternoon, unknown to me, Lt. Szymanski was pulling the machine guns and getting the men ready to pull out. 'Sergeant Bailey,' he said, 'you bring up the rear. Make sure everyone gets out.' He went down the ridge after giving me the last order I would receive in the23rd Regiment."

Bailey pulled out under grenade and rifle attack, running as fast as he could east along the high ridge. Eventually Bailey reached the main F Company positions on Hill 863, over 2000 yards along a ridge leading from Hill 1051.

"Someone in F Company came by and I asked it they needed men over in defense. He told me there were enough men there. 'Eat, replenish yourammo, and get some rest.'"

"There was a store of C rations and ammo there on top. I headed for the food. Another man was getting something to eat. I picked up more ammo for my rifle. I told the other man, 'Let's heat up the C rations.'"

"There were two F-80 jets approaching our position. The went over us at about 200 feet, heading out toward 1051. Within seconds, they could be seen in a turn east of 1051. They had not made any strike. They passed over us again."

On the third pass, something was terribly wrong. Bailey calmly related in his letter,

"... I saw the flashes from the lead jets' cannon. He was firing on us. The cannon shells were hitting all around us. My buddy dived into the foxhole with our cooking fire. I went into the foxhole on top of him. The jets went over our position again. The whole mountain seemed to be on fire. I wanted to get out of that fire. As I put my left hand down to get up, I felt my hand cook to the bone. I came out of a ball of fire and headed downhill."

In a terrified frenzy, Bailey ran through a minefield. A soldier stopped him, and demanded he sit down. The soldier asked what had happened, and Bailey said, "Our planes napalmed us." His letter ended with painful memories,

"...it started to dawn on me that I was burned other than my hands. He was staring at my face while talking to me. My legs were hurting also. My vision was affected but from what I could see my hands were badly burned. Later that evening I was taken to the bottom of themountain and evacuated by helicopter to a MASH unit. For me, the war was over."

Hoppy Harris was dug in with E Company on a ridgeline lower than Bailey, and still further east. Harris remembers the afternoon of May 17, 1951.

"...I see a napalm bomb drop from each plane and before they even strike I start to cuss. Then the napalm hits and balls of fire spew up and there is a great cloud of black smoke that billows up. Men come running out of it. Some run down the steep slope beating at the flames licking at their clothing, others try to pull off clothing as they run and stumble in panic toward us."

"The planes turn, and come almost straight toward us. I can't recall ever feeling as frustrated as I was that moment. I jumped into the bunker, readied the machine gun to fire free-traverse. I am determined to have a go at these simple bastards. But it seems half a dozen guys are yelling at me at once, yelling a dozen different things at once. I tear out of the bunker in a rage and see guys waving their field jackets and arms and yelling as if the pilot could hear them."

"It took me a long time to get over that incident. I really don't think I will ever completely get over it."

Hoppy Harris wrote a long narrative of his experience at the battle now know as the "May Massacre." On May 18, all units along the Hill 1051 ridgeline mass were overrun, and orders were given to fall back to the low ground. During an attempt by the 23rd Infantry to escape, the main road south was blocked by the Chinese. American soldiers blew up the ammo dump, destroyed vehicles, and set out on a brutal night march under fire with only what could be carried by each man. Wounded were carried on improvised stretchers by men stumbling in the dark.

From maps I provided, Harris had located his positions on the narrow ridge. Tom Ryan and I set out to climb up 600 meters to reach those positions. Tom was 42. I was 41. Certainly not young anymore.

Ryan drove the car as far as we could up a valley parallel to Harris's old position. I felt I couldn't write about the war if I did not try to climb these hills. I will never forget that climb.

Corn snow lay in patches on the ground, and other areas were icy. Pine needles blanketed the slopes. The path we had originally taken along a small stream stopped, and we had to climb up a steep face. We would take four steps, then slide down.

The slope changed from 30 degrees to between 45 to 60 degrees. I was gasping for air, grabbing every bit of vegetation for stability, never looking up. It was a matter of will-power and adrenaline.

We made a ridge spur a couple of feet wide, and headed toward the main hill. Tom took a nasty fall, and broke his metal detector. The spur we were climbing dropped off on both sides at least 200 feet. It was very important to test each foot fall, and make sure each handgrip on the bushes and trees was strong.

I slipped once, and my notebook slid down 50 feet. Goodbye notebook, there was no way I was going to climb down to fetch it. Tom knocked a rock loose, and it struck me in the leg. I decided to let him get ahead.

A half-hour later, we finally reached the ridgeline, and immediately found foxholes running in either direction. A bunker system was readily apparent. We discovered several obvious machine gun bunkers, fallen in now.

We could see a rock outcrop higher up the ridge. Tom took several coins from his pocket, and threw them into crevices in the rocks. I didn't have toask what he was doing. You do things sometimes that require no words. We were both on a personal pilgrimage.

It was all so easy, two middle-aged men climbing a ridge on a beautiful Sunday winter day in Asia in 1989. There were no exploding grenades, no screams of wounded, no blood flowing on the ground. None of our friends were dying. No frantic calls came over a radio. Our guts were not twisted in fear. We could not smell napalm, or the scent of cordite. The ground was not littered with brass casings, the air was not full of shrapnel.

I walked west on the ridge, eventually climbing higher. Hill 863 loomed before me. Tom stayed below at the rock outcrop, and I continued upward. It was again late in the afternoon, and he called out that we needed to go down before we got into trouble.

About a hundred yards below the peak of Hill 863, I stopped, exhausted, knowing I could climb no higher. I stood there, thinking about all the veterans I knew from the Korean War, remembering all the hours of interviews, the hundreds of letters, the outpouring of pain from total strangers. I remembered the late night calls from old soldiers who could not stand the pain any more, who had no one to talk to anymore.

I stood quietly for a few more moments, then yelled out the name "Phil Bailey". The words reverberated off the mountain.

I waited until I could no longer hear the echo, then started back down the ridgeline, in silence but for the sound of fallen leaves beneath my feet.

At Play

Tom Ryan took me to a small village south of Seoul.

Children were at play in a country free of war. Adults were playing a game on a straw mat laid out on the ground.

Only a few years earlier troops were fighting in this area a few miles from Inchon. On this day there were only smiles and concentration.

I was in Korea to visit battlefields and learn more about why my father. I was also there to see how Koreans lived and found joy in living.

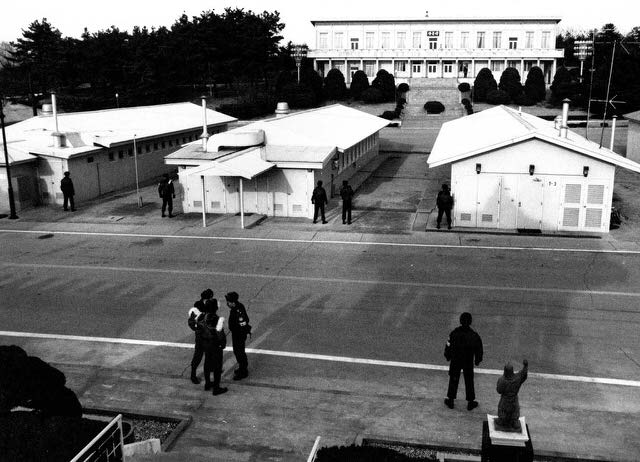

Panmunjom Truce Village

While I was in Korea, United States Eighth Army personnel exerted a tremendous effort to expose me to Korean customs and culture, to makesure that I did not just experience the "hamburger" culture of United States Forces Korea.

At Panmunjom, the site of negotiations between the North and South, I met American soldiers attached to the Military Armistice Commission.

Only yards away, North Korean soldiers took photographs of me taking photographs of them. I didn't feel tense or nervous, I was almost outside my body, just observing.

Sergeant David McGee, from Birmingham, Alabama, stood towering before me. McGee is a black man, strong, powerful, a symbol of all that is right about our country. Big men serve at Panmunjom.

I talked to Sergeant Edwin Brand of San Diego, California, and Corporal Melvin Over of Cherry Valley, Illinois. Each told me it was cold here, and boring in a way only a soldier could know. After the standard tour of a few weeks, it was Seoul, and some good times. I didn't find it curious at all that Brand would tell me that he often found it beautiful looking off into North Korea.

In the event of hostilities, McGee, Over, and Brand would be telegrams to their mothers, or visits from a uniformed officer knocking on a door. They would be dead, long dead, and only memories.

This is Panmunjom, and it is the real world, where people can die, and political ideals can be uniformly expressed in death. Americans have died here on the ground where these men stand every day of their tour. I don't feel self-conscious saying that I feel proud to have met these soldiers.

I also met Lee Ho Chul, a best-selling South Korean novelist, at Panmunjom. A crew from MBC, a Korean television network, was filming Lee at the Truce Village.

Lee's book, ""Panmunjom"", is a metaphor of North Korean and South Korean relations. In Asia, ideas are often expressed in symbolism. The story is about the relationship between a man and a woman. The man is a South Korean journalist, the woman a North Korean journalist.

The two journalists meet at Panmunjom, and both fall deeply in love.

But the love is impossible.

North Korea and South Korea are inextricable in love. The bonds between North and South are family bonds, blood bonds, bonds of a culture split in ideology. But the love is impossible. It struck me like a hammer blow what Lee Ho Chul was saying about peace on the Korean peninsula. But Lee was also saying that where there is love, there is a chance. Without hope, there is nothing but despair.

American soldiers occupy positions on high ground overlooking the Joint Security Area at Panmunjom in the Demilitarized Zone. I visited these positions with several officers and men of the United States Army.

It was another unforgettable experience.

I stood at the trip wire, the cutting edge of American military power in Korea. Here the 1st Battalion of the 506th Infantry Regiment of the United States Army Second Indianhead Division stands as a front line combat unit.

Two outposts, Collier and Ouellette, comprise the forward American elements. Kids, American kids from California, Kentucky, and points around the country man the bunkers and stand the constant patrols. Anti-personnel radar antennas spin, seeking out movement on the North Korean side of the Military Demarkation Line.

This isn't Hollywood, John Wayne is not here, and it is not easy duty. The bunkers are cold, without decent heating, and the soldiers are constantly in touch with their surroundings.

A tall young officer reminiscent of John Denver escorted me around Guard Post Ouellette. A bayonet flopped from his belt as he walked. He was calm without bravado, like the nice clean-cut kid down the street.

It was a very clear day looking out on North Korea. The Demarkation Line separating the two countries was only 50 yards away, and I was told American and North Korean patrols come within yards of each other in this area. Fences, barbed wire, and mine fields lay in front of me. It was a sobering thought.

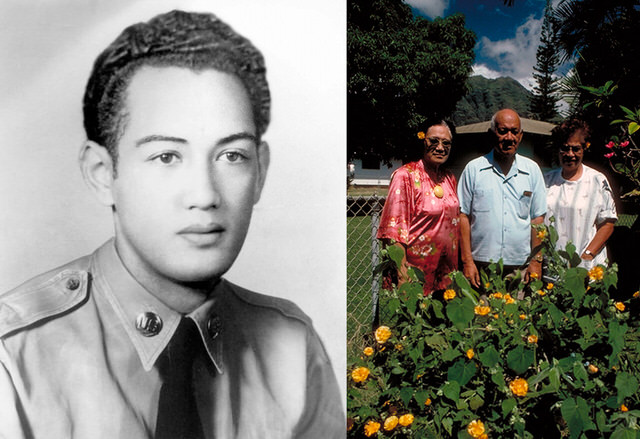

Hawaii

I caught a Korean Air Lines flight to Hawaii the next day. I had one more pilgrimage to make. I hadn't been back to my birthplace at Aiea Naval Hospital overlooking Pearl Harbor since I was a baby.

At the same time I was born in November 1947, a young Hawaiian was finishing his schooling at Waianae, on the southwest coast of Oahu.

Herbert K. Pililaau was a gentle boy known to everyone in his small home town. He was born October 10, 1928, into a family of nine brothers and five sisters. His father, William "Jack" Pililaau, was a famous Hawaiian cowboy.

On September 17, 1951, only days before his 23rd birthday, while serving with Company C of the 23rd Infantry Regiment, Pililaau was killed in action at Heartbreak Ridge.

Bob Krauss, a columnist with the Honolulu Advertiser, wrote a story about my attempt to find the Pililaau family, and calls flooded the switchboard of my hotel. Captain Joe Holt of the Honolulu Airport Fire Department made the first call at 5:30 A.M., and volunteered to guide me to the family.

We sat on a porch in Waianae, a soft wind blowing through the trees and bushes, the exotic smells of flowers everywhere. Coconut trees framed the driveway. The sky was a classic blue with fluffy white clouds, and the mountains in the distance made for a very peaceful morning. Agnes Pililaau Kim is known in the family as sister #5.

She told me her telephone had been ringing off the hook, people were saying some "haole" was looking for the Pililaau family. She said, "I felt good in my heart when I got the call you were coming. It was a good feeling to bring him back again. I felt what we say in Hawaiian, 'makala', awake. I felt alive."

William Pililaau, Jr.,#1 son, now 70, sat beside me. William is a Mormon, as are most of the family. He quietly remembered, "Herbert was a loner. He listened to classical music, didn't mingle. My other brothers and I were rowdy. Herbert was independent, he didn't get into trouble."

Sister #10, Mercy Pililaau Garcia, recounted a dream her mother had just before Herbert was killed. "He came to her in a dream, saying that he would die. He came to her calmly. He was her favorite son." Mercy said all his teachers loved him, he was a sweet boy. "He couldn't kill a fly, he was a soft kid."

When the family received news of the Congressional Medal of Honor, they actually could not believe it was the same boy they knew, it was so unlike him. President Truman presented the posthumous award to Mr. and Mrs. Pililaau in Washington, D.C..

The citation reads:

"Herbert K. Pililaau, as a member of Company C, distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and outstanding courage above and beyond the call of duty in action against the enemy. The enemy sent wave after wave of fanatical troops against his platoon which held a key terrain feature on Heartbreak Ridge. Valiantly defending his position, his unit repulsed each attack until ammunition became almost exhausted, and it was ordered to withdraw to a new position. Voluntarily remaining behind to cover the withdrawal, he fired his automatic weapon into the ranks of the assailants, threw all his grenades, and with ammunition exhausted, closed with the foe in hand to hand combat, courageously fighting with his trench knife and bare fists until finally overcome and mortally wounded. When the position was subsequently retaken, more than forty enemy dead were counted in the area which he so valiantly defended."

Agnes and Mercy took me to a park in Waianae named in honor of their brother. We walked across the street to the school-yard where Herbert once played. They talked of him as if he were walking there with us.

As I walked there on Oahu, I was thinking of that mountain in Korea where a gentle young man died covering his friends' withdrawal. I asked the sisters what the name Pililaau meant in Hawaiian. They said it means "stick together.""

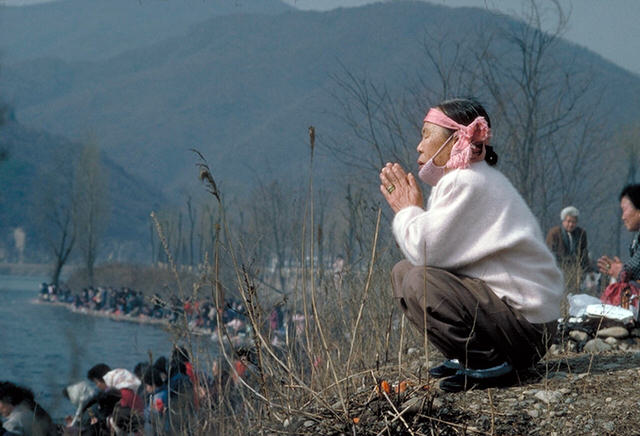

Rituals

Over 37,000 Americans lost their lives in the Korean Theatre of Operations. 8,177 Americans were declared Missing In Action or Unaccounted For Body Not Recovered. Countless Koreans died. The most brutal question is, was this sacrifice worth it?

For many years, I have been haunted by a photograph taken in 1950 by Associated Press photographer Max Desfor. The photograph depicts two Korean babies crying by the side of a road, their mother beneath them, her body twisted in death, caught in a crossfire.

In the South Korea of 1989, I saw hundreds of laughing and joking children in a schoolyard at Chipyong-ni, where 38 years earlier at that exact spot helicopters landed to evacuate wounded soldiers, and the dead lay in lines on the ground.

In the South Korea of 1989, by a river, I saw old women practicing beautiful rituals of an ancient culture. The water's edge was below me, and two elderly women struggled up the embankment. I held out my hand, and each in turn grasped me tightly. I helped them to sure ground. We made silent contact, and I shall always remember Korea from their smiles.Wherever I traveled in Korea outside Seoul, people came up to me to talk, often in broken English. Many apologized for the student riots.

I spoke with an old Korean man who had survived the war. He told me he had seen both good and evil from the Americans. He waved his arms before me, and pointed to the people around us and said, "We are alive now, and we have freedom we have never had before. Without America, we would have no chance to go our own way, right or wrong."